The Westminster Confession: a critique

The Westminister Confession of Faith is a 17th-century document which was drawn up at a particular point in Scottish and UK history. It continues to wield very significant influence on how presbyterian churches are run and what they believe. However it is a mixed bag.

‘We claim no infallibility for [the Confession], or for ourselves who declare our belief in the propositions which it contains. It is the Word of God which only abideth forever... It is open to the Church at any time to say, “We have obtained clearer light over one or other or all of the propositions contained in this Confession, we must review it; the time has come for us to frame a new bond of union with each other, a new testimony to the world.” If this freedom do not belong to us, then indeed we are in bondage to our Confession, and renounce the liberty wherewith Christ has made us free.’ ‘We claim no infallibility for [the Confession], or for ourselves who declare our belief in the propositions which it contains. It is the Word of God which only abideth forever... It is open to the Church at any time to say, “We have obtained clearer light over one or other or all of the propositions contained in this Confession, we must review it; the time has come for us to frame a new bond of union with each other, a new testimony to the world.” If this freedom do not belong to us, then indeed we are in bondage to our Confession, and renounce the liberty wherewith Christ has made us free.’

Rev. William Wilson (Free Church Moderator, 1866)

"I look on Catechisms as mere landmarks against heresey. If there had been no heresey, they wouldn't have been wanted. It's putting them out of their place to look on them as magazines of truth. There's some of your sour orthodox folk just over-ready to stretch the Bible to square with their Catechism; all very well, all very needful as a landmark, but what I say is, do not let that wretched, mutilated thing be thrown between me and the Bible."

Rev. Thomas Chalmers

(speaking on the right use of Confessions of Faith).

When the Church says to both ministers and people, “This is my Confession of Faith: if anything in it appear to you inconsistent with the Word of God, I am prepared to go with you to the Word of God to settle the matter”, then does the Church speak according to her place.

But if instead of this she says, “This I have fixed to be the meaning of the Word of God, and you cannot take any other meaning without being excluded from my communion; and to entitle me to exclude you I do not need to prove to you that what you hold and teach is contrary to my Confession of Faith”; I say, if the Church of Christ use this language she no longer remembers her place as a Church.

Rev. John Macleod Campbell

(deposed in 1831 by the Church of Scotland for preaching

‘assurance of faith’ and ‘unlimited atonement’)

Most [Church of Scotland ministers] do not hold whole-heartedly to the Westminster Confession of Faith. They may have subscribed to it at their ordination, but most did so never having even read the Confession. None of us ever received lessons in its theology.

Preamble: Preamble:

This is the second in a series of articles which were prompted in the summer of 2009 by the question of Sunday sailings to the Hebridean island of Lewis. The issue – by no means to the only one, locally or universally – is tied up with how we understand the Mosaic Law and how the church responds to that view.

It was felt then, and indeed is still the case, that a superficial response would merely reiterate what has been so often said on both sides of the debate – that is regarding whether or not disciples of Christ are ‘under the law’. Accordingly the first article in the series gave an overview of (some of the major) Covenants in the Old Testament (aka the Old Covenant; but more correctly the Old Covenants) in order to establish a biblical foundation to build upon. It is strongly recommended that the article ‘A Covenant-Keeping God’ is read in conjunction with this writing, as it has a fundamental relationship to what follows.

This present article gives a background and overview to a very important period in the formative life of the reformed church in Scotland: the focus is on a creedal document which was formulated in the middle of the 17th century and is, in substantial part, an outworking of a theological construct termed 'Covenant Theology'. [The latter is a 'prism' through which some interpret Scripture and should not be confused with the covenants contained in the Bible.]

The Westminster Confession of Faith (Note 1.) was essentially drawn up by a committee of English ‘Westminster Divines’ with a handful of senior Scottish churchmen carrying ‘assessor’ status (which allowed them to debate, but not to vote). It has been, and continues to be hugely influential but also the cause of much controversy and debate.

In spite of its English origins, it was only adopted in that country for a short period of four years. However, and in stark contrast it has and continues to the present day to have enormous influence on the structures, beliefs, government, ministries, expectations and traditions of the Presbyterian churches in Scotland and all over the world.

.

Caveat

It is no purpose whatsoever to create controversy or upset through this writing. Neither, however is it the intention to shrink back from expressing concerns in an unambiguous fashion. Accordingly euphemisms have been avoided for the sake of maintaining clarity.

Additionally and in this context, no significant effort will be expended in this essay on the biblical (supportable) parts of the Confession’s text. Neither (at this stage anyway) will everything that is written be annotated with source references. (The reader is encouraged to do his/her own research; with the ultimate reference being the Word of God. The supplied references relating to the WCF will be expressed in Roman numerals. Note 2.)

Summary

The Westminster Confession of Faith contains much solid teaching on core Christian doctrines. The document has been immensely useful as a statement of many biblical and foundational truths; and as a counter to false teaching since its inception.

The Westminster Confession of Faith is permeated with unsupportable statements and also very significant ‘holes’. It is – at once and in parts – deficient, erroneous, ambiguous, unbiblical and extra-biblical. It also strays from defining doctrine into setting out what was and is merely ‘opinion’ – including also matters of church law. It has the characteristics of what one writer described as being a ‘paper Pope’, and become as another has said a ‘golden calf’. In this writer’s view, it has ever been deficient and in error.

Essentially the WCF is a 'child of its time'; a veritable ‘curate’s egg' – a mixture of good and bad; a compendium of Truth, error and omissions; and, at least in the present day, serves the church very badly in a number of areas of Christian life and church practices.

The document has caused continuing division amongst those who hold the Word of God in high regard; and has also been demonstrably incapable of maintaining Truth amongst those who don’t. There are very few indeed who believe it all; and probably none who can, from a biblical base, justify all that it contains.

------------------

Introduction and Background

All the Presbyterian churches and denominations in Scotland link back to 1560AD and the Reformation – as a spiritual movement to correct the abuses, excesses and errors within the (Roman) Catholic Church at that time. In that year, John Knox and the five other reformers (all with the Christian name John), formulated a creedal statement entitled the Scots Confession. It was completed in four days. All the Presbyterian churches and denominations in Scotland link back to 1560AD and the Reformation – as a spiritual movement to correct the abuses, excesses and errors within the (Roman) Catholic Church at that time. In that year, John Knox and the five other reformers (all with the Christian name John), formulated a creedal statement entitled the Scots Confession. It was completed in four days.

This ‘Confession’ was however superseded over 80 years later by a document entitled the Westminster Confession of Faith (WCF) – drawn up from 1643, on instruction issued by the London-based parliament from whence the document’s title derives. Yet in spite of its Westminster origins, the Confession had, as the summary states, only fleeting place in England and in the Anglican Church.

It is also worthwhile noting that the ‘scripture proofs’ were only added on later instruction from the Westminster parliament. Many of these Bible references (aka ‘proof texts’) – appended in postscript fashion – have tenuous relevance to the body text.

Paradoxically however, and though the cause of much debate and controversy through the centuries since, the WCF survives and is maintained universally as the subordinate standard of Presbyterian churches in Scotland and indeed around the world (Note 3).

The backdrop to the Confession was both religious and political. In Scotland, the reformers (Covenanters) wished not only to eradicate all traces of episcopacy and earthly-sovereign headship, but also saw a chance to extend the Presbyterian system of church government into England. (The Covenanting ideal being that of one church in the nation; with one king under the one true God.)

Meanwhile the anti-royalist parliamentarians in England saw advantage in enlisting the Scots in the puritan struggles be break free from the Church of England with the King (Charles I) as its supreme governor. Additionally however there was the perceived need to reduce the threat of Irish-Catholic intervention in the first English civil war (1642 – 1646). After much haggling, these separate and distinct agendas were built into a document called the ‘Solemn League and Covenant’ (dated 1643, and not to be confused with the earlier purely-Scottish ‘National Covenant’ of 1638) – the title reflecting the dual perceptions and purposes.

[The cross-border alliance however later broke down when, in 1649, the English assassinated Charles I (who was not merely the English monarch, but Scotland’s king also); and because the dominant grouping amongst the parliamentary puritans rejected presbyterian church polity in favour of congregationalism. Subsequent to this turn of events, the Scots then ‘changed sides’ and obtained King Charles II signature on the Solemn League and Covenant. The occasion giving rise to Oliver Cromwell’s famous plea to the Scots: “I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken.”]

It was within this ambivalent and fluid context that the Westminster Confessions were formulated.

Doctrinal issues

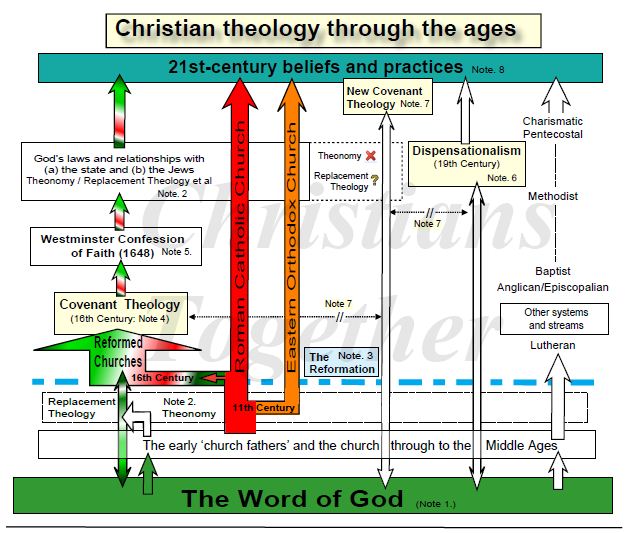

<click on image below for Theology Chart>

From a doctrinal standpoint, much of the WCF is based on a theological construct commonly known as Covenant Theology. The effect of this system of theology on Christian doctrine is profound. From a doctrinal standpoint, much of the WCF is based on a theological construct commonly known as Covenant Theology. The effect of this system of theology on Christian doctrine is profound.

Three of the very important derivative doctrines relate to the view that the church is now ‘Israel’ (i.e. Replacement Theology/Supercessionism); the way ‘the Law’ is understood and applied in NT times (theonomy); and end-time expectations (eschatology).

There are many other issues relating (inter alia) to how the church is governed; the relationship with the state; baptism; clergy/laity distinctions; the Sacraments and the administration of same; double predestination which consigns some to hell; and how to understand the prophetic scriptures.

[In the context of the ‘Drilling Down’ series, further articles will be written (d.v.) relating to church/state relationships, the Mosaic Law and legalism.]

As affirmed above, the venerated document contains much that is sound and fundamental to the Christian faith. Indeed (as also stated above) in the context of previous centuries, the WCF has served as an ‘anchor in the storms’ of the post-Reformation Presbyterian churches in Scotland. However, the WCF has created storms of its own; and controversies remain to the present day.

Over and above these issues, there is a broad agreement amongst many (including the most ardent of its supporters) that the WCF is – simultaneously – seriously deficient, while also being erroneous and unbalanced in many of its thirty-three chapters of creedal statements. (Note 4.) These difficulties are compounded by the fact that the WCF contains 17th-century dictates on church law, and is also dogmatic on subjects that in fact attract a range of differing opinions across the Bible-believing spectrum of the church of Christ. This latter category of problem includes particular views on who should receive baptism; the beliefs relating to Christ’s second coming (eschatology); the way of salvation (soteriology); church government (ecclesiology/prelacy) and church/state relationships.

One of the WCF’s most controversial statements labels the Pope as the Antichrist (which pre-supposes a particular eschatology on which there is no universal agreement).

There are four very significant problems There are four very significant problems

relating to the Westminster Confession:

-

the first of these relates to the inadequacies, errors and unscriptural assertions made within the document itself.

-

the second major issue is the extent to which the WCF is regarded by some as sacrosanct and beyond question (in a de facto sense denying the ‘semper reformanda’ maxim).

-

the third relates to the extent to which the WCF seeks to conform the Christian ‘life and doctrine’ to some significant and unbiblical patterns.

-

and the forth major problem is the extent to which the WCF has contributed to the denominational divisions - even within the Presbyterian denominations which subscribe to it (at one level of commitment or another).

Concerning these matters, the WCF is questionable in the following areas

(and this list is not exhaustive) –

-

teaching the transcendence of God but failing to include the immanence of God (cf WCF II (ii); , Rom 8:15, Gal. 4:6, Eph 1:5, Matt 1:23, Heb 1:3)

-

contradicting itself by describing God as ‘without passions’ and yet ‘hating sin’ (WCF Ch II(ii)

-

allowing an assumed ‘two-covenant’ hermeneutic of 'works' and 'grace' (WCF VII(ii, iii, iv, vi; XXI(i; vi)) to formulate doctrine on a range of issues (e.g. relating to the understanding and the application the ‘law’; and the place of Israel with respect to God's purposes.) (See below also.)

-

dogmatically prescribing the mode of baptism (WCF XXVIII (iii)) and the ‘baptism’ of infants (WCF XXVIII (iv))

-

assuming the state has a duty to support the church (WCF XXIII (i)) (More in a subsequent article on church/state relationships – the principal cause of the 1843 Disruption.)

-

restricting the ‘sacraments’ to those (two) which Jesus ordained (WCF Ch XXVII (iv) cf. James 5:13 – 15)

-

teaching a two-tier clergy/laity distinction in the priesthood of all believers (see above notes re the administration of the sacraments; and WCF Ch XXXI (ii))

-

teaching double-predestination (God pre-ordaining/consigning some to Hell) (WCF X(iv))

-

creating a lack of assurance of salvation (as a result of the above)

-

failing to teach on the (major) doctrine of the Holy Spirit as the third person of the Godhead

-

failing to include any teaching on the biblical injunction of the Great Commission i.e. no mention of evangelising the lost

-

declaring the Pope as being the definitive antichrist (based on a particular post-millennial eschatology) (WCF XXV (vi))

-

a minimalist, inadequate and limited conception of worship (whilst seeking to define same)(WCF XXI(i and ii))

-

creating extra-biblical distinctions between the OT laws (i.e. civil/ceremonial/moral: XIX (iii; iv; v)) and thereby...

-

selectively forcing some old covenant laws upon Christian believers (who are accountable under the New Covenant laws of Christ rather than the 613 OT laws). (WCF XXI (vii, viii) (More in a subsequent article d.v.)

----------------------------

Closing remarks

Thus you nullify the word of God by your tradition that you have handed down.

And you do many things like that." Mark 7:13

Two of the principle tenets of the Reformation were (are?):

‘Sola Scriptura’ (Scripture alone) and ‘Semper Reformanda’ (continually open to reform).

It is the author’s earnest hope and prayer that the 21st-century Presbyterian church will abide by, and be seen to be abiding by these principles, by re-visiting and critically examining the Westminster Confession of Faith as its principal subordinate standard – for the good of the church as the body of Christ, but supremely for the glory of God and the extension of His Kingdom. Amen.

Footnotes:

1. The text of the WCF (with Scripture references) can be found at www.reformed.org/documents/wcf_with_proofs/index.html

Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia, is a very convenient and quick reference source. What it lacks in comprehensiveness it gains in neutrality.

Notwithstanding the above, the use of 'hot-links' has been minimised in this article so as not to disadvantage anyone reading the text in hardcopy form. However, on-line reading allows 'pop-up' Bible texts to appear on 'mouse-over' of the Scripture references.

2. The original document used Roman numerals and the internet-based copies use the same.

3. Splits in the Presbyterian church(es) in Scotland around the turn of the 19th/20thcentury were caused by varying degrees of adherence to the WCF. Qualifying statements and subsequent ecclesiastical legislation have variously modified the extent to which strict adherence is required to all the WCF contains. The terms ‘fundamental doctrines’ and ‘substance of the faith’ have been developed and employed without any definitions of same.

In 1989 the APC grouping was formed when the Free Presbyterian Church disciplined an elder (Lord Mackay of Clashfern) for attending friend’s funeral service (Mass) in a Roman Catholic church – which the WCF believes to be the system of the Antichrist.

A de facto split in the Free Church of Scotland last year revolved around what is or not permissible in ‘worship’ (as ill-defined yet narrowly-constrained by the WCF).

The current fragmentation of the Church of Scotland is producing seceding groups which are (still) wedded to the Westminster Confession in spite of the latter’s failure to maintain a biblical orthodoxy.

Most recently controversy has again arisen due to an ‘ecumenical’ service in the isle of Lewis involving Presbyterian clergy along with a Roman Catholic priest (as an ‘agent of the Antichrist).

4. In the light of continuing controversy and disagreement relating to the WCF the Church of Scotland's Panel of Doctrine prepared a number of papers on the subject for presentation to the Church. These essays were published under the title The Westminister Confession in the Church Today [St. Andrews Press 1982].

5. As stated above, subsequent articles will (d.v.) aim to look at Church/State relationships: the OT laws; Legalism; and Sunday/Sabbath observance (in that order) as part of the ‘Drilling Down’ series.

6. The above is a ‘work in progress’. It will most likely be embellished, augmented and corrected (if and where necessary). It is the second in a series; the first being an article entitled ‘A Covenant-keeping God’.

Logged-in site members can use the 'Response' facility below. Any comments from non-members of the site should be made directly to the Editor, and these will be taken account of in the final version.

Indeed considered responses made at this (earlier) stage are viewed as being much more helpful in order to facilitate an ordered discussion at a later date if this indeed transpires. It would be helpful in any responses to quote Scripture.

<top>

|